3 Some Odd Bods

Mwanza, like many other towns, had its share of odd fellows and the somewhat eccentric. There were three, who were particular favourites of the town kids, though one of them was rather dangerous because of his violence.

Dhamjibhai was an elderly man who lived near the lake in the Makongorro area. He ran a little duka, a shop, where he sold loose foodstuff like rice, flour, salt, dried lentils and grain, cooking-oil, kerosene and other items including lollies and local home-cookies.

Regularly, at five in the evening he left his home, which was the back of the duka and made his way to the Indian vishy, an eating-house, in Mwanza Road, the main street. Here he met his cronies and had the daily game of cards on the veranda of the vishy. These whist games were serious affairs, and the greasy dog-eared cards played with great gusto and loud colourful comments. On many an occasion words and arguments about various moves burst forth to the great amusement of the onlookers. The kids allowed to watch the tamasha, the fun, had to keep their distance and remain respectful.

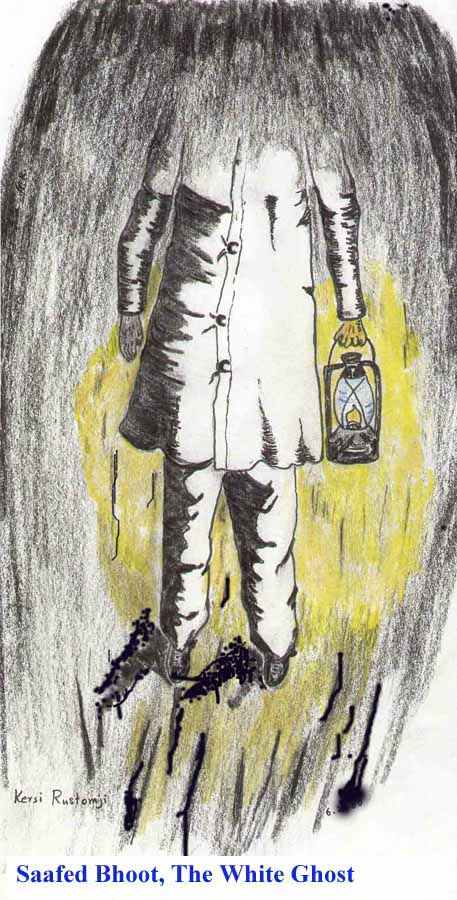

The most interesting performance came from Dhamjibhai. Whenever he trumped a suite, he pulled up his tall thin self high above the table, slammed his trump card down calling out, "Maar salah ku, maar salah ku, beat the rascal, beat the rascal." Naturally, he became known as maar salah ku. Every time the kids went to his shop for a lollypop or a cookie, they slammed their coin on his counter and called out maar salah ku, and pretending anger, Dhamjibhai served them. However, he was also known as saafed bhoot, the white ghost, though we dared not call him that to his face. This was because of his nightly return home after the card games.

Except for a black round Moslem skullcap, Dhamjibhai dressed in a knee long white coat over white trousers, both rather gray from long wear and dirt, and wore old worn and unpolished black shoes. He always carried a hurricane lantern for there were no streetlights, except on the main road. As darkness commenced and ended the card game, Dhamjibhai prepared for his long return home.

He sat his lamp on the table, dug in his coat pocket, pulled out a box of matches, and without fail rattled it near his ear. Raising the glass chimney he lit the lamp adjusted the wick and shook the match off. Then the little cap came off and the sparsely haired scalp received a brisk rub. With the cap replaced, he picked the lantern, always in the left hand, bade his mates a farewell, and left for the two-kilometre walk back to the duka, shop and home.

As he made his way along the dark streets, the lantern light glowed around his white trouser legs and about halfway up his white coat. The rest of him disappeared in the darkness. From a distance, it was a weird sight to see a pair of whitish legs walking along the road, so he was dubbed the saafed bhoot, the white ghost.

|

Dhamjibhai on his way home after card

games |

In the morning or in the evening during the news time everybody listened to the radio, especially the broadcasts from the BBC, London and Nairobi, Kenya. Naturally, everybody was aware or knew of what the broadcasts said and it was all a matter of talk or discussions in the town. However, our friendly secret informer thought differently. For some reason or other, he felt that whatever was broadcast it was meant for only the friendly, trustworthy and loyal persons. That none of the news had to reach anyone else especially the jasoos, the spies, who lurked in the town. For was not Mwanza after all a part of Germany, as the Germans had once ruled Tanganyika.

He became especially agitated if someone tried to eavesdrop as he whispered the news. Immediately he dashed off to the police station and reported the incident forthwith. We kids had great fun with him for we deliberately sought him out during his secret news rounds and one or the other sneaked up to him. As soon as he spotted the eavesdropper the rest started to chant, po...lice, po...lice, and followed him to the police station. As he climbed the stairs to go in everybody waited, for soon he would return with a cop and from the top of the steps try to point out the eavesdropper. At this juncture, everybody called out, radio... radio... radio, and ran off. Then Radio having been assured by the police that they would seek out the jasoos, returned to further spread the top-secret news. He never became upset if called Radio. In fact, whenever the kids called out to him he smiled and nodded his head in acknowledgement.

In contrast to Dhamjibhai and Radio, Salimu was rather frightening and completely different. Nobody knew or could tell what tribe he belonged to or if he had anybody. Yet he was known all over the town as he rummaged through the rubbish bins and the market garbage pile. Unlike the other poor of the town he never begged and did not go from house to house seeking alms or food. He wore the dirtiest and the grubbiest of the rags, for there was not an untorn garment on him. If he was given clothes, he always tore these apart and donned the pieces over his old filthy rags. He never washed and he was always covered in dirt. He even rubbed soil on his limbs and body and hair. The hair was quite long but it was solidly matted in dirt and often had dead bugs or beetles in it together with bits of grass and twigs; similarly, his beard was a nest of grubs and grass picked up from his overnight sleep in some grass or scrub.

Often he slept under the date palms in a patch of grass across from our garden. He did not speak or talk to anybody nor did he ask for what he wanted. If he needed a drink, he simply walked to the nearest garden tap and helped himself. He was quite short but with a stocky build and was very strong. The tale was that he broke rocks at the local quarry from time to time but had his wages deposited with the proprietors, as he did not accept the money.

Salimu however was very hot tempered and became very violent if he was teased. Nobody knew whether he was really an epileptic or not; but if anybody shouted, kifaffa, epileptic, or Salimu ni kifaffa, Salimu the epileptic, he turned extremely angry and violent. He threw stones at the perpetrators and chased them. He flung whatever came to hand and he snarled and breathed through his teeth. There were many times when some innocent persons were hurt by his onslaughts, which I too did not escape.

One evening as we made our way to the club, I was walking some distance behind mum and dad. As I rounded the corner of the vishy I saw Salimu coming at me in full fury. He wielded a large stone and before I could run back around the corner, it hit me very violently on the chest. It knocked me down, and in both pain and fright at Salimu's approach, I screamed and screamed.

Dhalla Abdulla who owned a shop across the street happened to notice the incident. With an axe handle he always kept under the counter, he rushed out and intercepted Salimu who was rapidly shuffling towards me. With the axe handle raised above his shoulder, he confronted Salimu and spoke to him. I was too terrified and crying aloud as I lay on the ground, to know what was said but after some words Salimu turned around and walked away. By this time, some people had gathered around and as Salimu left, somebody picked and took me to Dhalla Abdulla's shop, while someone else went to call mum and dad. I had a large black bruise on my chest and was very sore for a week or so. Although I was home from school, it was not much fun, as there was little I could do, and I certainly was not able to clamber up any trees.